The dominant civilizations and pop culture of the West have always maintained a nostalgic affinity for tribal cultures. Unfortunately, so often it seems our society is more attracted to the idealized symbols that native people represent while ignoring the actual and current struggle faced by all native people across the planet.

Tribal cultures embody a connection to natural forces and the earth seemingly lost by the West. New age movements often borrow heavily from Native American traditions, which represent a bridge to a more sane relationship between nature and human existence.

Resonance with tribal cultures underlies much of The Farm’s development, which could be described as the rebirth of tribalism in a western European society. This connection to the values held by Indigenous people has been exemplified throughout the Farm’s history and continues to flourish through real actions.

Beginning at Birth

The dedication to natural childbirth formed a bond not just between the couple and their newborn, the couple and their midwives, but for the community as a whole. Birth became the link fusing the raw forces of nature with family and community, the essence of tribal relations.

In the mid-70s, members of Awkwesasne, the nation of Native American Mohawk straddling the U.S. and Canadian border in upstate New York, began communicating with The Farm, expressing a desire to receive training in midwifery in order to bring those skills back to their community. Several women and their families came down to live in Tennessee and begin a hands-on apprenticeship. At the same time their husbands and a single man from Awkwesasne also came down to live on The Farm and receive training as Emergency Medical Technicians or EMT’s with The Farm’s ambulance service.

In 1978 an event took place called The Longest Walk, a gathering of Native American tribes from across the U.S., calling attention to the economic conditions on reservations, broken treaties and to raise awareness among the general population and even more specifically among Native American youth. The Longest Walk began on the west coast with a couple hundred participants with the intention to physically traverse all the way to Washington D.C., picking up additional representatives from various tribes and Indian Nations as the group passed through different states. As the Longest Walk converged on the many hundreds of small towns and cities across the country, the presence of Native Americans would generate press and media coverage that spread the message and in its own way helped put pressure on bureaucrats in Washington D.C. managing Indian affairs.

It could be said The Longest Walk was loosely assembled by a group of Native Americans leaders organized as the American Indian Movement or AIM. AIM’s leadership was made up of people who were, to various degrees, in sync with the progressive leftist political movements of the times and their presence played a vital role in the spirit of the event. Aggressive actions, such as the occupation of the prison on the island of Alcatraz in 1971 and the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington D.C. in 1972, brought media attention and helped galvanize the group but also made it the target of the FBI. The 1973 protest/occupation by AIM members of the monument to the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, resulted in a standoff shootout with the FBI lasting 71 days, ultimately culminating in the death of two of AIM’s members before an agreement to disarm could be negotiated.

The Longest Walk was like nothing the people of the U.S, had ever seen. Known to most people only through television westerns and John Wayne movies, the country’s Native Americans were suddenly very visible as an ethnic sub-culture that had been submerged within the country, now cast into the light by the hundreds of Indians walking through Middle America. The Walk was a rallying call especially to “traditionalists,” those whose lives symbolized a resistance to assimilation into Western culture in their communities. It provided an opportunity to showcase tribal identities beyond the pow-wow gatherings held in many regions of the country with larger Native American populations.

The Longest Walk brought together Native Americans of all types and ages, from veterans of World War II and Viet Nam to aging grannies and multigenerational families. It appealed especially to the young, who were on the front lines of unemployment and the air of hopelessness so prevalent on the reservations.

When The Longest Walk reached Pennsylvania they were about 700 strong. Sensing the power and importance of this event, The Farm decided to send up an ambulance to help support the walkers and their mobile community. The Farm had one member who was Native American, a Muscogee Indian named Mark who would be the person in charge of the ambulance and crew which included the EMT trainees from Awkwesasne and one member of The Farm’s radio crew whose main job was to assist with communications.

I had the great honor of serving as the radio communications technician and ambulance driver on The Longest Walk.

The ambulance had a CB radio and walkie talkies were passed out to various representatives among the walkers and their support vehicles. This allowed them to call The Farm ambulance for any emergency. Fortunately the crew never had to deal with anything too serious, primarily heat exhaustion and blisters. The ambulance also had a police scanner, which made it possible to track the communications about the Walk by the authorities. The Walk was under heavy surveillance, with helicopters flying overhead and police escorts a daily presence.

The Longest Walk enter the Mall in DC – photo by Plenty International

The march into DC took about 6 weeks with the group setting up camp often for several days to a week at various points along the way. Word was getting out and the final encampment in DC had about 4000 Indians and 1000 white supporters. The Farm sent up a couple dozen additional representatives including Stephen and his family to be part of the many rallies taking place across the city. There was a concert featuring nationally famous Native American performing artists like Buffy Saint Marie, a benefit boxing match with Mohamed Ali, speeches on the steps of the capital and around the city. The energy was very high. It was the first and only time in history that Indian people had converged in numbers this large at the seat of power and the colonial government that had taken their lands and committed genocide on their people.

On one afternoon the march arrived in front of the FBI building for a press conference. A podium and public address system with a microphone were set up and suddenly it became evident there was no place to plug into power. The FBI guys on the other side of the barred entrance just smiled. Fortunately, one of The Farm’s support vehicles had its own generator and we were able to supply the electricity needed by the PA. For once the voice of the tribal people was not silenced by the government.

The opportunity to be involved with this unique assembly of Native American elders was a very eye opening and transformational experience. At the same time the close contact dissolved illusions, with the awareness that Native Americans carry the normal faults that all humans share, placing the problems within The Farm’s social dynamics in perspective.

Land of the Maya

Without question the most significant connection to tribal cultures by The Farm Community took place after its newly formed relief and development organization, Plenty, sent a team down to Guatemala after a devastating earthquake in 1976. What The Farm discovered, was a centuries old Mayan culture that was still very much intact, with the Indigenous Maya representing over 75 percent of the country’s population. In many ways it was like stepping back to a time where the relationship of people to the land and their tribe remained as the focal point for human existence. This extended direct contact with an ancient Indigenous culture had a dramatic effect on The Farm and provided a living example to the community, clearly illustrating how tribe and family are interconnected.

The work in Guatemala was the biggest project The Farm had ever taken on. A camp was established to function as a base of operations. Over the duration of the project as many as 200 people were dispatched from The Farm to be involved in the relief work. Now in addition to living the dream of creating a new utopian society, each person in the community could feel they were actually making a difference in the world and in the lives of others. Daily communications via the ham radio from the camp in Guatemala back to Tennessee gave everyone the sense that the entire Farm community was united behind the effort.

In the months after the initial state of emergency had passed, members of The Farm serving as Plenty volunteers began to recognize that the earthquake was only the beginning of the problems the Mayan people of Guatemala faced on a daily basis. The work the members of The Farm were doing seemed to be just scratching the surface.

San Bartolo

For the first two years, Plenty volunteers worked in the town of San Andrea Itzapa, where downtrodden farmers served as virtual slaves on large plantations. When Plenty’s service to the poor began to draw the ire of local government officials around Itzapa, the entire camp was moved to the state of Solola and a small village called San Bartolo, two hours deeper into the mountains.

Everything was different in Solola. Most of Solola’s population worked as independent farmers tending small plots scattered across the steep mountainsides. The vast majority of the Mayan population wore colorful handmade clothing woven on primitive backstrap looms, a form of weaving that had been handed down for centuries. Although still quite poor, the people had dignity and a sense of pride, a radiance that had an immediate appeal to the Plenty volunteers.

Solola was like a paradise on earth. Located further up in the lush, green highlands at 7000 feet, the area lived up to the phrase “land of eternal spring,” with year round temperatures never going above the mid-70s in summer or going below 40 in winter. San Bartolo had a view which looked out over Lake Atitlan, one of the largest and highest altitude natural bodies of water in the world, formed by a volcanic crater. Five volcanoes surrounding the lake were visible from the camp, including one that was active called Fuego (fire) which regularly spewed out plumes of smoke and ash. There was a magic about the place that was tangible, almost surreal.

The villagers of San Bartolo were just as curious about the hippies as the Plenty volunteers were drawn to the Mayan culture. The new setting was very much in the middle of the aldea or village. Plenty had leased a large home to serve as the new base of operations and it came with a Mayan caretaker family living just a few feet from the back door of the kitchen. Other village homes were less than a stone’s throw away. It was a very direct and deep immersion in the Mayan way of life. Teenage girls from the village enjoyed visiting the camp and cooking on the large restaurant-sized gas stove in the kitchen, teaching the Plenty people the art of making tortillas by hand. Women from the village began sharing their knowledge on how to do the weavings with the backstrap looms. Real friendships developed.

From 1978-1980, I served as the radio operator at for Plenty in Guatemala.

Beyond what we were experiencing through our work on the projects, it was the day-to-day living amongst the people that brought home the real heart of tribal culture. Wrapped in the cloak of Christianity, there was an ancient appreciation of the divine which emphasized humility and gratitude. At the center of every home was the altar, 4 to 5 feet wide and a foot deep, dotted with burning candles illuminating a crammed odd assortment of figurines, objects with special meaning, trinkets and bottles of Coca-Cola. The alter was both mysterious and captivating, an everyday reminder of the spirit that underlies all things.

On holy days the air was alive, awakened by the powerful smell and thick smoke of copal, an incense made from evergreen tree sap. The aroma carried with it the muttered prayers of gray haired elder, perhaps a prayer for good harvest, the sacred corn that would fill the family’s stomachs and allow them to survive another year. Corn was the rhythm of the seasons. Corn was the foundation, quite possibly the only food at every meal, there because the seeds were planted, tended by the fathers and the sons, and the rains came and the sun shined each day. So much has been lost in our modern world, our tie to the cycles of life, the intimate knowledge of our sustenance, hardened by cement and blurred by speed. The memory of what we had forgotten was still breathing in the Maya.

Across the small valley below the Plenty encampment was a Mayan family compound, its borders outlined by dried cornstalks defining its dimensions. Around its perimeter were a number of small huts, walls made from the same stalks of corn, each covered by a palm thatched roof, bedrooms for the many families; the brothers and sisters, along with their spouses and several children, one for the patriarch and matriarch, the father and mother of the clan. The elders, the old, no longer able to work in the fields, no longer able to carry the water, the fire wood, but still part of the family circle, making their contribution, to tend the fire, to pat the tortillas, just as they had always done, together, the people of the corn.

Throughout each day the women would sit together in the courtyard, to weave, to create the cloth, the very clothes on their backs, the clothes of the family, thread by thread, the wooden spindle passed back and forth, tamping row by row, an inch a day, perhaps two. The richness of color in the “tela,” the cloth, was beyond beautiful, a textured warmth no machine made clothes can ever come close to. Clothes made by hand, by dedication, by love.

It was a privilege to be served around the fire, the honored guest, a hot cup, “un café,” a coffee roasted on that same hearth, of beans from bushes down the hill, a flavor smooth and rich, to share the smiles, the humor of getting to know each other.

In the developed world we take so many things for granted. We assume our water is free of parasites and that its supply is virtually unlimited. When water is in short supply and must be carried often a very large distance, one doesn’t think about using it to wash hands. Flush toilets simply do not exist. Living side by side with the Maya, Plenty volunteers could see firsthand the invisible oppression the absence of clean water imposes on a people.

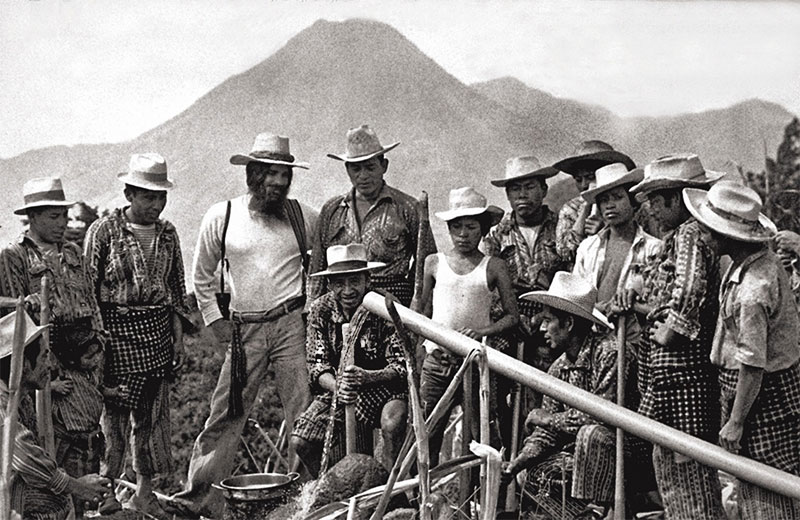

From 1978 to ‘80, Plenty volunteers brought clean water to thousands living in village across many parts of the country. Instead of simply putting a band aid on the symptoms of poverty, Plenty’s water projects in Guatemala truly improved the quality of life. But real help is not about the great white benefactors bestowing aid to the needy. There has to be a shared respect.

The water project for San Bartolo, Guatemala – photo by Plenty International

In conjunction with the water projects, Plenty volunteers would host meetings to educate Mayan villagers on the importance of clean water and the need for proper sanitation. A microscope was set up so that people of a village could look through to see slides full of wiggling parasites. The link between bugs in your belly, diarrhea and abdominal pain was made easy to understand. A healthy man is able to go to work and support his family. Kids who are not sick are able to attend school. A people who are kept strong are more likely to hold on to their culture.

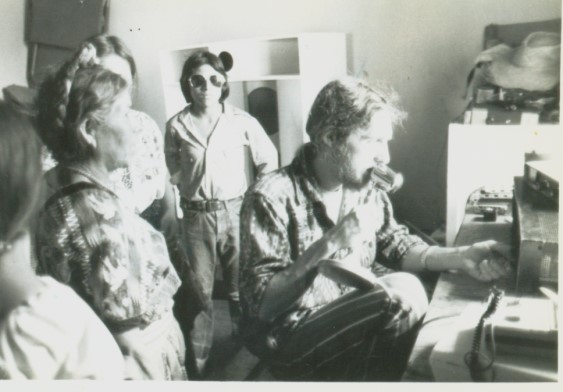

Deborah, with Leah and Jody and another red headed kid from the Farm, see the results of the water project. Deborah was the lab technician who set up our microscope to show folks in the village the amoebas living in the water from the creeks.

In the village of San Bartolo, there was a special night, a celebration near the end of Plenty’s time there which seemed to capture the mutual friendship and bond that had grown between the hippies and the Maya, two very different tribal cultures. Plenty and village volunteers had just completed work on a new school. All of the dignitaries, officials and politicians who had made their way to the village for the official dedication had gone.

The band played, a single marimba worked by three musicians, each with his part, the bass, the alto, soprano, the full organic tones of wood vibrating through the air. There are no sad songs on the marimba. Small groups danced in several circles, holding hands. A woman would go to the center and spin around, reaching to take off a man’s hat and put it on her head, spinning again, a twinkle in her eye. Then returning the hat and grabbing another, teasing, laughing, joyous, under the stars. Together, as one, the dancing went on into the wee hours of the night. No one wanted to end.

The Political Climate Changes

Ever since the overthrow of the civilian elected government by a CIA orchestrated coup in 1954, Guatemala had been under the rule of long line of generals. After the Cuban revolution in 1959, the U.S. military had increased its presence and influence in Latin America, suppressing any populist movements through harsh intimidation, eliminating (murdering) any union, student or religious leaders speaking out on behalf of the poor.

In a very real way the earthquake of 1976 had upset the checkerboard and put the entire country in a state of chaos. Desperate for aid on all fronts, the cracks in Guatemala’s infrastructure and control left spaces where groups working on behalf of the poor could squeeze through and organizations like Plenty were able to establish a presence.

Life in Guatemala changed dramatically after the election of Ronald Reagan as President of the United States. Even before taking office, it appeared as if deals were being made and the word was clear: use any and all means necessary to maintain control. For the Plenty volunteers, the idyllic life in the Land of Eternal Spring was be overshadowed by a dark cloud.

The fear intensified with the emergence of the death squads known as the White Hand, named for the mark left on doors at the homes of the disappeared. In conjunction with the overt military campaign, the real counter insurgency work was being done outside the realm of accountability. Day or night, armed men would arrive murdering anyone even suspected of not being in full support of the government, their mutilated bodies dumped in the center of a village to be an example of what would happen to those who questioned the military’s authority. Entire were villages burned to the ground, turning anyone who survived into homeless refugees. Ravines with scores of dead bodies began to become commonplace, reported weekly in the country’s newspapers with pictures and in graphic detail.

One story in particular heard at the time demonstrated the brutality and sent a clear message to the intent of the oppression. In a town just across the lake from our location in Solola, a party was being held for two students who had just graduated and were returning to serve their community as doctors. Armed, masked men arrived, took the two students away and murdered them. It was clear that the life of anyone helping the people was at risk.

Farm men with their long hair and beards fit the profile of the Marxist revolutionary. Plenty people dressed in the same hand woven clothing worn by the Mayans, a visible blatant statement of solidarity. Virtually all of the projects were in direct support of the country’s Indigenous population, working with the poorest of the poor.

Everyone in the camp began to question how much longer the work could continue? There was an illusion of security, believing that it would cause too much controversy in the U.S. media for any Americans to become a target. However as stories circulated about American Catholic nuns and priests being tortured and murdered, even that barrier seemed to be dissolving.

In the late summer of 1980 the decision was made to leave. The Farm’s greyhound bus arrived in September to transport everyone back to Tennessee. It was a very sad good bye.

Where and whenever possible, Guatemalans with the necessary experience were hired to implement and complete ongoing projects. Over the coming decades, Plenty would continue to receive proposals and take on various projects in Guatemala, using the model of working with local organizers rather than sending down teams of American volunteers. The Guatemala experience set the tone for Plenty’s mission, to work in support of native peoples and their struggles.

Stateside

Back in the U.S., the participation on the Longest Walk established a number of contacts and led to long term friendships in Native American circles, opening the doors to future Plenty projects. One of the first to get traction was at the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota.

The concept was simple: Help people take control of their lives and put their energy into something positive, a home garden. The request for funds and assistance came from a resident on the rez who would go to the home of anyone wanting a garden, till their ground and supply seeds and plants to get them started. The first year there were five, the next year 25 and by the fifth year 200 gardens throughout the reservation, and the number continued to double in size. Plenty was able to be the conduit for funds from other nonprofits that wanted to help empower native peoples but did not have the direct connections to facilitate projects.

Over the last several decades Plenty has continued to nurture this relationship with Pine Ridge, sending teams of carpenters and students from The Farm School to build a house, do home repairs around the reservation, and to develop the infrastructure for a camp where volunteers could stay during their time in South Dakota. The work has had multiple benefits, supplying a helping hand to those in need, and a way to give volunteers the chance to connect with something deeper, the link to a resonance with the earth and spirit that Indian people have carried for thousands of years.

Native Voices

The culmination of these collective experiences also made it possible for The Farm to serve as a microphone for the voices of Native people. In the late 70s, the community’s Book Publishing Company began printing and distributing the works of Indigenous authors in its catalog of titles. Over the ensuing decades the number of books continued to expand until the company had an entire catalog dedicated to Native Voices, becoming one of the primary publishers for Native American authors in the world. The numbers are small, no million sellers here, but these books serve an important niche audience and keep the avenues open for the words of Native people to remain alive and relevant.

The Farm as a Tribe

It’s been estimated that around 5000 people have lived and spent significant time on The Farm community, most during the early communal years. The experience transformed people in a way that left them forever changed, a connection that persists as meaningful and real despite the passage of time. During the period leading up to The Changeover there were more than 1200 people living on The Farm and the breakdown of the communal economy caused the dispersal of hundreds far and wide. But what has endured so many decades later goes beyond friendship.

Dictionaries define the word “tribe” as people with a common culture or character, a social structure that establishes links between families. The Farm went beyond the hippie subculture to become a unique social experiment that created emotional bonds which remain alive in all who have been touched by their common connection. It spans through multiple generations woven ever more tightly by the cross pollination of families through second generation marriages and subsequent grandchildren. In seeking ways to define these relationships the word “tribe” comes closest. Understanding The Farm as a tribe takes in both the strengths and the dysfunctional weaknesses that exist within families and tribal communities, recognizing that the relationships go beyond random even in their imperfection.

In that sense, The Farm Community is seen by its tribe as the reservation, the sacred land which symbolizes the greater whole. The land serves as a unifying vessel which holds the memories, the dreams, and the energy of everything that has taken place within its boundaries.

And like the tribes of Indigenous people today throughout the world, the vast majority may never live on that land, yet they still are part of that common essence which links them to something larger than their immediate family. It also takes in the idea that there are people who share the same values and may be considered members of the tribe who have no immediate connection to The Farm, distant clans with their own set of experiences and circles of community.

As The Farm’s communal period recedes farther into its own historical perspective and as its founding generation gradually passes on and departs from this plane of reality, the question remains open: What core values will persevere? Can this tribe survive the outside and internal pressures that challenge its existence, beyond the founding generation? Will the subsequent generations be able to maintain and forge new bonds that have kept the community intact throughout the previous decades of its history? Only time will tell.